Building a Premier League Clustering Model

In my previous post, I introduced my Premier League Team selection tool, used to match MLB fans with Premier League teams. In this post, I detail the data collection, analytical approach, and visualization techniques I used to create the visualization.

Initial Data Collection

To perform this analysis, I collected data on the following characteristics of both EPL and MLB teams:

- Weighted average of team record for the past 25 years

- Number of titles and runner-up finishes in team history

- Number of player awards won in team history (EPL: PFA Player of the Year and Young Player of the Year, MLB: MVPs and Cy Youngs)

- Age of Stadium

- Stadium Capacity

- Average price of a beer at the stadium

- Previous season’s offensive and defensive metrics (EPL: Goals Scored/Allowed, MLB: Offensive WAR and Pitching WAR)

Gathering data and cleaning it for analysis proved to be the most time consuming aspect of this project. Since I set out to compare MLB teams to Premier League teams, I wanted to ensure consistency of data and continuity of observations. I gathered most of my baseball data from BaseballReference.com, Wikipedia, and a study on MLB fan costs. Most of my EPL data came from Wikipedia, PremierLeague.com, and a Daily Mirror fan cost study. I used a combination of data downloads and web scraping to gather the data.

Data Preparation

After gathering all the data, I performed a considerable amount of data cleaning and transformation to prepare for analysis. One major challenge was handling missing seasons in the previous 25 years for both MLB teams (as a result of new teams) and EPL teams (as a result of promotion/relegation). To handle these seasons, I simply assigned each season the minimum team win percentage in baseball and the minimum number of points in EPL in their respective leagues. Next, I put all team names in a standard format and converted them to the appropriate data type. Once I’d finally gotten the data sets in the right format, I merged them together to create one data frame for MLB teams and one for EPL teams. With my prepared data frames in place, I was ready to perform data analysis.

Modeling Approach

Unsupervised learning involves grouping data without knowing in which class it belongs. When performing more traditional data science, we know what class we want to predict. For example, if I want to predict which MLB teams make the playoffs, I’ll build a model using the historical stats of teams that did and did not make the playoffs. In this case, since we don’t already know how MLB teams and EPL teams are similar, we don’t already know what we want to predict.

While it’s true I could build a model to predict MLB teams based on the data I collected, then apply this model to Premier League teams, I feared three downsides:

- I might not be able to accurately predict MLB teams, which would result in a bad model for EPL teams

- Since there are 30 MLB teams, even with a perfect 1:1 match, 10 MLB teams would not have a companion EPL team

- Given the nature of sports leagues, there are often many middle of the pack teams, so predicting based on my data might have assigned a significant number of teams to a small number of teams.

For these reasons, I decided to rely on unsupervised learning, to instead group “like” MLB teams, then apply that model to EPL teams to see how they fit the groupings. Performing this sort of grouping proved challenging as well, as I’ll detail further.

Building a Clustering Model

While there are a few forms of unsupervised learning techniques, I decided to focus on clustering. Clustering involves grouping observations based on the distance between each of their variables. There are different ways to determine the groupings, but in general, we measure the effectiveness of clustering by the density of clusters (how close the observations in each cluster are to each other) and the distance between clusters (how far each cluster is from the other clusters).

When clusters are easily separable, this can be simple, for example, grouping EPL players by their positions. Based on stats on where players spend time on the pitch, it will likely be easy to classify players into positions. However, for data without easily separable clusters, it can be challenging to separate classes in a meaningful way.

To build my clustering model, I tried three approaches: K-Means Clustering, DBSCAN, and Hierarchical Clustering.

K-Means Clustering

K-Means Clustering works by grouping clusters based on the distance from some number of k points, then iterating until the optimized distance between points is achieved. In K-Means clustering, a number of groups is selected, and the model will separate them into groups algorithmically. Since I didn’t know exactly how many groups I wanted, I tried varying numbers until I found a number of clusters that did a good job of separating the data, but balanced cluster density. K-Means gave me 8 clusters, which seemed to be a good method of dispersion.

DBSCAN

DBSCAN stands for Density-based spatial clustering of applications with noise and is another clustering technique. DBSCAN arrives at a number of clusters using its algorithmic approach, measuring the distance between observations and other observations. When observations are within the radial distance of other observations and meet a minimum neighboring threshold, they are grouped into the same cluster. When one cluster runs out, the algorithm generates a new cluster. This process continues until every observation has been clustered or determined to be too far from other observations to assign to a cluster. I tried varying inputs for the radial distance and minimum number of points for MLB teams, but wasn’t able to group teams to more than 3 groups.

Hierarchical Clustering

In Hierarchical Clustering, a mapping of the distances between each observation and the other observations is created. This web is organized into a decision tree-like graph, that converges with each observation grouped together at it’s end. This graph is called a dendogram and helps visualize how far each observation is from the other points. From there, a threshold between groups must be decided and much like in K-Means Clustering, clusters can be separated by selecting a number. However, with Hierarchical clustering, a distance is specified, which can somewhat arbitrarily leave observations in disparate groups. Furthermore, Hierarchical Clustering typically works best in situations where there is a distribution between observations. For example, if we wanted to cluster all English clubs that participate in the FA Cup, we might use Hierarchical Clustering, since it would better group the clubs in each division.

Choosing a Clustering Model

After running through each model, I decided to go with K-Means using a k of 8 since K-Means ensured the best spread of clusters with the most practical application. While the density and separation metrics may have been slightly better with other k options and other techniques, clustering metrics are meant to be used as guidelines, not rules. With that in mind, 8 clusters did the best job of separating as many MLB teams and EPL teams as possible.

While unsupervised learning can sometimes be inexact, my groupings certainly pass the eye test (Yankees and ManU) so I feel confident in their conclusiveness.

Visualization Structure

Given that the teams in my analysis are based in cities, I knew I wanted to incorporate a map in some way. While people often want to use maps because they think they’re cool (which let’s be real is true), it’s important to consider if it will actually add to the analysis. In this case, I considered using maps for both MLB and EPL. However, I decided to use a map only for the EPL and not the MLB, with my rationale being that for my audience of MLB fans, using a map of the US would not add any new information, but a map of the UK would. Knowing exactly where an EPL team is located visually, adds an important element of information that can help a user better understand the team they’ve selected.

Since the EPL teams are meant to be the focus of the visualization, but need to be narrowed through the MLB teams, I made sure they consumed the majority of the space. The bottom three quarters of the visualization feature the EPL teams, with the middle two quarters, dedicated to team exploration. With the top quarter, I decided to display MLB teams in a scrollbar style, to simplify the experience for the user and clearly indicate that selecting an MLB team would flow down screen to narrowed choices for EPL teams. Choosing an EPL team in the map, provides a tidy overview of the club and it’s characteristics in the left side bar, and allows a user to quickly learn about clubs. Lastly, the live table at the bottom provides additional context on the quality of the selected club.

Building the Visualization

To construct the visualization, I had two main time-consuming tasks. The first was connecting logos to teams from both leagues and the second was displaying the geographical locations of each club in a meaningful way.

Showing Team Logos

To address the logos challenge, I had to save each logo to the folder on my computer that contains Tableau Shapes (Documents/My Tableau Repository/Shapes), then assign them appropriately.

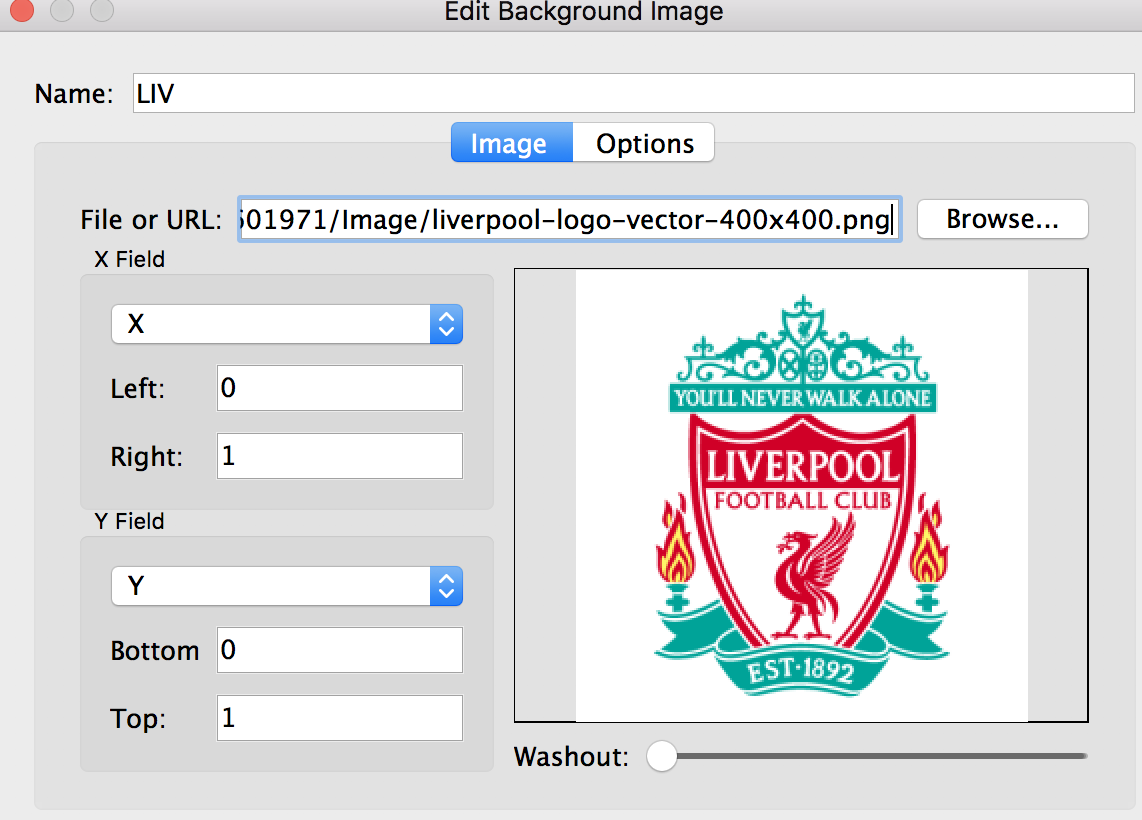

I went through a similar process for the EPL teams, with one additional step. To display the team logos in their own sheet, in high resolution, for Tableau Public, I had to set the logos as the background, conditional on the selection. To do this, I created calculated fields “X” and “Y” and set them equal to 1. Next, I went to Map>Background Images and selected my data source. When the menu popped up, I selected “Add Image” and began the process of adding each team logo. To add a logo, I added the file by clicking “Browse” and linking to the file. then I added the calculated field “X” to the X field axis and “Y” to the Y field axis. I set the minimums equal to 0 and maximums equal to 1. This ensures that background image scales properly. Lastly, I clicked on “Options”, and checked “Always Show Entire Image”, then hit “Add”. There, I chose the EPL team field, and chose the team for my selected logo. This ensured that that specific logo, only shows when that specific team is selected. I proceeded to complete these steps for each team until I had all the logos set up.

Displaying Geographical Location

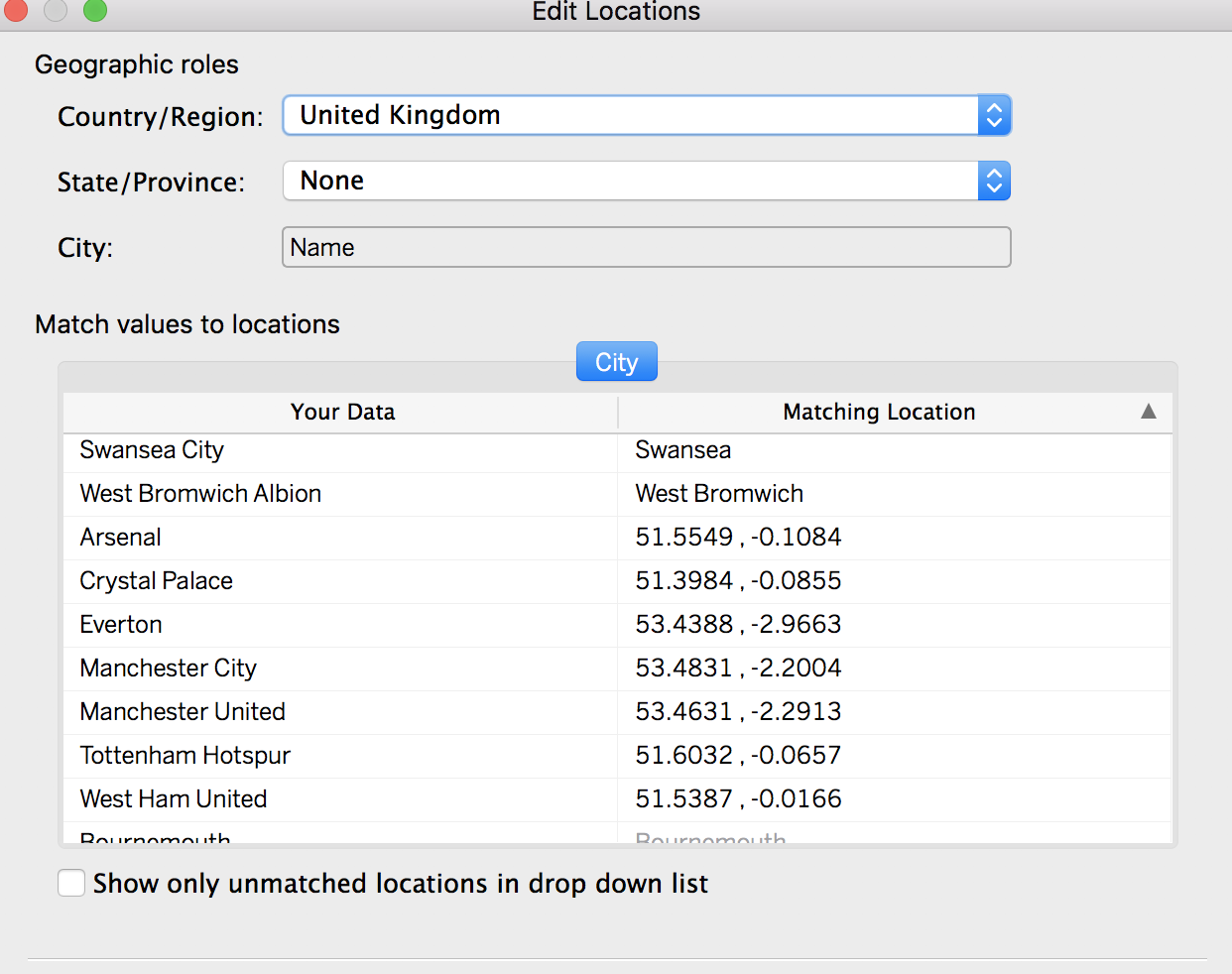

While many of the teams had their city attached to them, for a few cities, the location was ambiguous or overlapped another team. For example, in London there are 6 teams in the greater metro area. To display their logos without overlapping each other, I manually entered the latitudes and longitudes of each stadium, ensuring that the logos wouldn’t overlap each other. To do this, I clicked on Map>Edit Locations, then manually inputted the coordinates for the appropriate stadiums.

Updating the League Table

The last step to complete my visualization was setting up the live data table. It’s not truly live, but it is automatically refreshed every Thursday, using a combination of the Football Data and Google Sheets. Thanks to the Tableau Google Sheets connection, the visualization automatically updates every day at 11 am.

Conclusion

The entire project took me the better part of two weeks to complete, with much of my time spent on data collection and preparation. While it was time intensive, I thoroughly enjoyed the process and challenge. Further, I learned a few cool pandas tricks and honed my web scraping skills. I also learned a great deal about clustering, which will serve me well in the future. Lastly, I always enjoy working in Tableau and this time was no different. Each time I use it, I get better at structuring my visualizations and adding new features.

As mentioned previously, MLB is only the first league I plan to incorporate and I hope to update this post in the future with a new post on teams from another Big 4 American Sports League.